🥦 Nutrition & Nutrients

Endocrinology

Insulin

December 31, 2025

Share

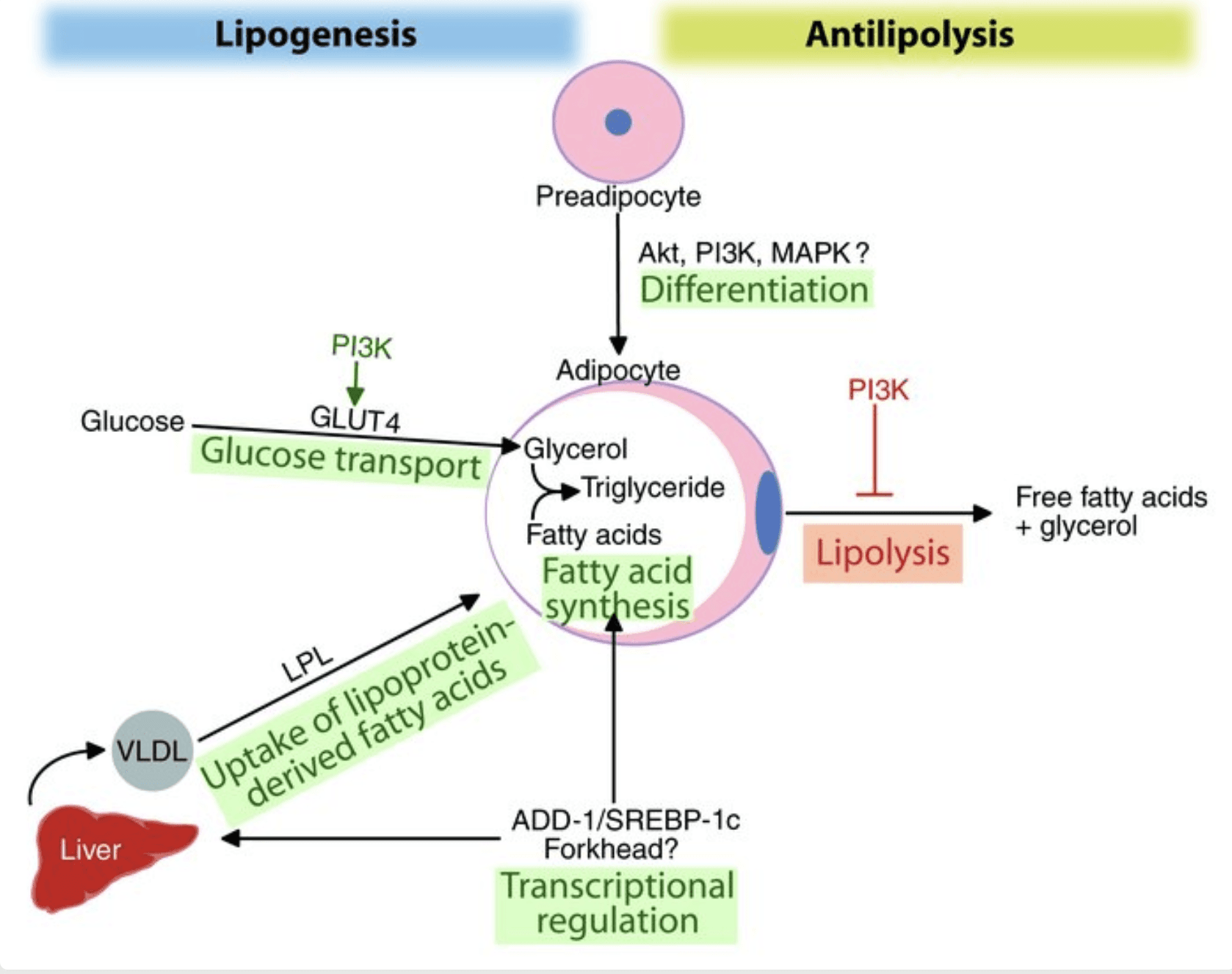

Upon eating, insulin triggers glucose transporters (GLUT4) to move to the fat cell surface, pulling in blood glucose which is then used to form glycerol and fatty acids for new fat molecules . Insulin also activates lipoprotein lipase, an enzyme that releases fatty acids from circulating lipoproteins, facilitating their uptake into adipocytes. By blocking hormone-sensitive lipase, insulin is the body’s most potent anti–lipolytic hormone, rapidly suppressing the release of stored fat. Through these mechanisms, insulin promotes the accumulation of triglycerides in fat cells, increasing their size (hypertrophy).

Beyond acute metabolic actions, insulin influences fat cellular development. It fosters adipogenesis – the differentiation of precursor cells into mature adipocytes. Insulin’s signaling upregulates key adipogenic transcription factors like PPARγ and SREBP-1c, which drive the gene expression needed to create and fill new fat cells. Insulin “promotes adipocyte triglyceride stores” by both stimulating preadipocyte-to-adipocyte differentiation and enhancing lipogenesis in mature fat cells.

In essence, insulin orchestrates a shift into energy storage mode: turning sugar into fat, pulling in available fatty acids, and locking away existing fat by halting its breakdown.

Figure: Insulin’s multi-pronged effects on fat cells (adapted from Kahn & Flier 2000 ). Insulin stimulates glucose uptake and lipogenesis, increases uptake of fatty acids (via lipoprotein lipase), and induces adipogenic factors (e.g. SREBP-1c) to promote fat storage. Concurrently, insulin strongly suppresses lipolysis (fat breakdown).

Fat Tissue Needs Elevated Insulin to Grow

A growing body of evidence indicates that without insulin, significant fat gain is biologically difficult. Insulin’s presence is essentially permissive for fat storage – fat cells do not readily enlarge or multiply in its absence. A striking example comes from animal research: Blüher et al. (2002) created mice lacking insulin receptors specifically in fat tissue (so-called FIRKO mice). These mice were resistant to obesity – they had very low fat mass and remained lean even when aging or when overeating, unlike normal mice. The study demonstrated that insulin signaling in adipocytes is “critical for development of obesity”, meaning that without insulin’s signal, fat cells could not accumulate normal lipid stores. In other experiments, blocking insulin action impaired the ability of pre-fat cells to mature and store fat. For instance, fat precursor cells grown without insulin show poor lipid accumulation and fail to fully differentiate into fat-filled cells. These findings reinforce that elevated insulin is a prerequisite for substantial fat tissue expansion.

Human observations align with this concept. Untreated type 1 diabetics (who lack insulin) classically experience weight loss and cannot maintain fat mass due to unchecked lipolysis. Conversely, medical insulin therapy often leads to weight gain as fat storage resumes. Insulin is so central that even in insulin-resistant states (like early type 2 diabetes), the body often compensates by producing extra insulin, which preserves fat storage capacity. In fact, even when muscle and liver become insulin resistant, adipose tissue may remain sensitive to insulin’s fat-storage command, so elevated insulin still promotes fat accumulation. Clinically, hyperinsulinemia (chronically high insulin levels) is associated with weight gain and difficulty losing fat. The bottom line is that consistently elevated insulin provides a continual signal to grow fat tissue, whereas without that signal, fat cells have a much harder time growing or surviving.

Moderating Insulin to Manage Body Fat

Given insulin’s key role in driving fat storage, strategies to moderate insulin levels or effects can aid in managing body fat. Reducing excessive insulin spikes and fasting insulin can tilt the body toward fat-burning rather than fat-storing. Both lifestyle interventions and medications have evidence-based benefits:

Lifestyle and Dietary Interventions

Lower Glycemic Diets: Eating foods with a low glycemic index (that release glucose slowly) helps blunt large post-meal insulin surges. Low-GI diets led to lower fasting insulin levels and more weight loss in obese individuals compared to high-GI diets . By avoiding rapid sugar spikes (from refined carbs or sugary foods), one can prevent the sharp insulin elevations that drive fat storage. For example, in a 12-week study, a low-GI diet reduced post-meal hyperinsulinemia, easing stress on insulin-producing cells, whereas a high-GI diet kept insulin levels higher despite weight loss. Emphasizing fiber-rich vegetables, intact whole grains, and other low-GI carbohydrates (or even adopting low-carbohydrate diets) can improve insulin sensitivity and promote fat loss.

Exercise: Regular physical activity is a powerful way to improve insulin function and lower baseline insulin levels. Exercise, especially when combined with weight loss, enhances insulin sensitivity of muscles and fat tissue, meaning the body requires less insulin to manage blood sugar . Studies show exercise-centric lifestyle programs can even reverse hyperinsulinemia in overweight individuals. Muscle contractions during exercise allow glucose uptake independent of insulin, and after exercise, insulin action is improved for hours. Over time, trained individuals tend to have lower fasting insulin. Additionally, exercise directly burns calories and can create a caloric deficit, reducing fat stores. A session of moderate-to-vigorous exercise also acutely lowers circulating insulin and increases counter-regulatory hormones, creating a hormone environment favorable to fat burning during recovery.

Intermittent Fasting: Intermittent fasting (IF) approaches (such as 16:8 time-restricted feeding or the 5:2 diet) deliberately incorporate longer stretches without food intake, during which insulin levels drop low. Fasting lowers insulin, which in turn unlocks fat stores for use as fuel . In low-insulin conditions, the body shifts to burning stored fat (increased lipolysis and fat oxidation). Research on IF shows it can lead to weight loss and improved metabolic markers. For example, one study on the 5:2 fasting diet (5 days normal eating, 2 days very low calories per week) noted significant reductions in body weight and a decrease in fasting insulin and glucose levels in participants. By giving the pancreas “breaks” from constant insulin secretion, IF may improve insulin sensitivity as well. Individuals who practice fasting protocols often experience reduced hunger over time and better insulin regulation. However, it’s important that any fasting or diet regimen be personalized and done safely, ideally with professional guidance, especially for those with diabetes.

Pharmacological Interventions

Metformin: A first-line medication for type 2 diabetes, metformin helps lower insulin levels and improve insulin sensitivity. Metformin works primarily by reducing the liver’s excess glucose production and by making tissues more responsive to insulin. The result is often a drop in circulating insulin, especially in people with insulin resistance or prediabetes. For instance, a clinical trial in adolescents with hyperinsulinemia showed that 6 months of metformin therapy cut their fasting insulin levels by nearly half (from ~19 µU/mL to 11 µU/mL) on average. By tamping down insulin (and blood sugar) spikes, metformin can reduce fat storage signals. It tends to be weight-neutral or modestly weight-reducing, in contrast to some other glucose-lowering drugs. Metformin may also curb appetite slightly and promote a shift toward fat burning via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in the liver and muscle. In various studies, metformin therapy modestly reduces body weight or at least prevents weight gain; for example, the metformin-treated group in the adolescent trial above had a significant BMI decrease while the placebo group did not. Beyond diabetes, metformin is often used off-label in conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) that feature hyperinsulinemia.

GLP-1 Agonists (e.g. Semaglutide): GLP-1 receptor agonists are a newer class of medications that dramatically improve both blood sugar control and weight loss. Semaglutide (originally developed for diabetes at lower doses and now used at higher dose for obesity) works by mimicking the gut hormone GLP-1, which increases satiety and insulin release when appropriate. This dual action leads to reduced caloric intake and better-balanced insulin dynamics. In clinical trials, weekly semaglutide injections yielded remarkable weight loss – about 10–15% of body weight on average – in people with obesity, far more than with placebo. The weight loss is driven largely by appetite suppression and lower food intake, which in turn can lower insulin resistance. Interestingly, beyond its appetite effects, semaglutide appears to enhance insulin sensitivity in tissues; studies indicate it helps muscle and fat cells uptake glucose more effectively by increasing GLUT4 transporters, thereby alleviating insulin resistance . Importantly, GLP-1 agonists do not cause constant insulin elevation – they trigger the pancreas to secrete insulin only when blood glucose is high, and they suppress the counter-hormone glucagon. The net effect is improved glycemic control without excessive insulin levels at baseline. Patients on semaglutide often see fasting insulin and glucose levels decrease as they lose weight and their body becomes more insulin-sensitive. Besides semaglutide, other GLP-1 analogs (like liraglutide) similarly promote weight loss and metabolic health. These medications are changing the treatment landscape for obesity and type 2 diabetes, though they are costly and can have side effects (most commonly, gastrointestinal upset). They illustrate how targeting the insulin pathway (indirectly, via appetite and incretin hormones) can produce substantial fat loss.

In summary, maintaining healthy insulin levels is central to controlling body fat. Insulin is indispensable for nutrient storage, especially fat deposition, which is why chronically high insulin can lock the body into fat-storage mode. The encouraging news is that by modifying diet, exercise, and using specific medications when appropriate, one can lower insulin spikes and resistance, thereby “unlocking” fat stores. Strategies like reducing high-glycemic carbs, increasing physical activity, and intermittent fasting all improve the body’s insulin profile and tilt the energy balance toward fat loss. For those with type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome, drugs like metformin and GLP-1 agonists address the underlying hyperinsulinemia or insulin effects, helping to restore a metabolic environment where fat can be lost. Ultimately, the combination of a mindful lifestyle and, if needed, medical therapy can moderate insulin’s influence, enabling better management of body weight and metabolic health.

References:

Kahn, B.B. & Flier, J.S. (2000). Obesity and insulin resistance. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 106(4): 473–481. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC380258/

Blüher, M. et al. (2002). Adipose tissue selective insulin receptor knockout protects against obesity and insulin resistance. Developmental Cell, 3(1): 25–38. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12110165/

Blüher, M. et al. (2002). Adipose tissue selective insulin receptor knockout protects against obesity and insulin resistance. Developmental Cell, 3(1): 25–38. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12110165/

Giorgino, F. et al. (2019). Insulin and insulin receptors in adipose tissue development. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(3): 759. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6387287/

Saltiel, A.R. & Kahn, C.R. (2001). Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature, 414: 799–806. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11742412/

Janssen, J.A.M.J.L. (2021). Hyperinsulinemia and its pivotal role in aging, obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(15): 7797. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/22/15/7797

Spalding, K.L. et al. (2008). Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans. Nature, 453: 783–787. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18454136/

Perin, L. et al. (2022). Low glycaemic index and glycaemic load diets in adults with excess weight: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 35(6): 1124–1135. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35704216/

Solomon, T.P.J. et al. (2011). A low-glycemic index diet combined with exercise reduces insulin resistance, postprandial hyperinsulinemia, and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide responses in obese, prediabetic humans. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 94(5): 1385–1393. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20980494/

Sutton, E.F. et al. (2018). Early time-restricted feeding improves insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and oxidative stress even without weight loss in men with prediabetes. Cell Metabolism, 27(6): 1212–1221. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29754952/

Atabek, M.E. & Pirgon, O. (2008). Use of metformin in obese adolescents with hyperinsulinemia: a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, 21(4): 339–348. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18655569/

Rena, G., Hardie, D.G. & Pearson, E.R. (2017). The mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia, 60: 1577–1585. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28776086/

Wilding, J.P.H. et al. (2021). Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 384: 989–1002. Available at: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2032183

Müller, T.D. et al. (2019). Anti-obesity drug discovery: advances and challenges. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 18: 527–552. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31086318/

Wen, X. et al. (2022). Signaling pathways in obesity: mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 7: 298. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41392-022-01125-1

Blogs and Insights