📌 Conditions & Clinical Guides

Iron

Exersice

October 26, 2025

Share

Absorption, Distribution and Regulation

Iron is an essential trace mineral required for oxygen transport, energy production, brain function, and immune health. In the body, iron exists mainly in two forms — haem iron, found in animal foods and easily absorbed, and non-haem iron, found in plant foods and absorbed less efficiently.

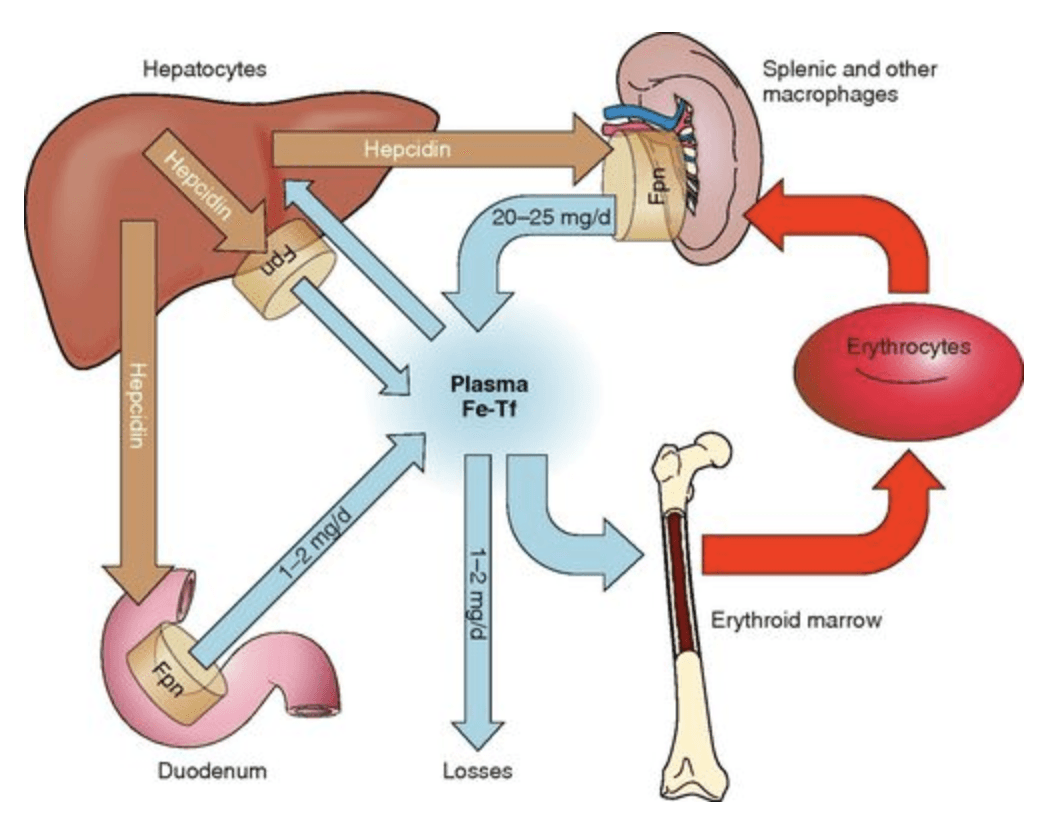

After absorption in the duodenum (small intestine), iron enters the bloodstream via a transport protein called ferroportin (Fpn). It binds to transferrin (Fe-Tf), which carries iron through the plasma to tissues that need it, such as the bone marrow (for making red blood cells) and the liver, where it is stored as ferritin.

(Ganz, 2013)

The diagram above shows how iron circulates between different body compartments:

Dietary absorption (1–2 mg/day) occurs in the duodenum.

Recycling (20–25 mg/day) is the main source of iron, as old red blood cells are broken down by macrophages in the spleen and their iron is reused.

Losses (1–2 mg/day) occur naturally through the gut, skin and sweat.

Hepcidin, a hormone made by the liver, acts as the master regulator of iron balance. When iron levels or inflammation rise, hepcidin increases, blocking ferroportin and reducing absorption and release of iron into plasma. When iron is low, hepcidin decreases, allowing more iron to enter circulation.

Iron is required to build haemoglobin (a protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen from the lungs to tissues throughout the body) and myoglobin (a protein in muscle cells that stores and releases oxygen during muscle contraction). Iron also contributes to mitochondrial energy production, brain function and immune resilience. In the bloodstream, excess iron is stored in a protein called ferritin. Although ferritin is often thought of as an “iron bank,” it also responds to inflammation and stress. This article explores how iron status influences exercise capacity and how, conversely, intense training can deplete iron stores.

Why Iron Matters for Athletic Performance

Oxygen transport and energy production

About 70 % of your body’s iron is bound to haemoglobin and myoglobin, which ferry oxygen from your lungs to working muscles and hold it for use during contractions .

Iron is a cofactor for enzymes in the electron‑transport chain; without it, mitochondria cannot generate ATP effectively. Even mild iron deficiency can reduce maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂max) and force the body to rely on anaerobic metabolism .

Studies in heart‑failure patients and athletes show that iron deficiency reduces exercise capacity long before anaemia develops. Women with ferritin <15–35 μg/L who received intravenous iron experienced significant improvements in VO₂max and running time . Similar benefits have been observed in recreational exercisers after iron supplementation .

Neuromuscular and cognitive benefits

Iron participates in myelin (a fatty sheath that surrounds and insulates nerve fibres, speeding up electrical signal transmission in the nervous system) formation and neurotransmitter synthesis. Deficiency can cause fatigue, slower reaction time and difficulties with concentration. These symptoms reduce training intensity and recovery . Low ferritin has been linked to chronic fatigue and mood disturbances in athletes .

Who is at risk?

Athletes – particularly endurance runners, cyclists and swimmers – have iron‑deficiency rates between 15 % and 35 % in women and 3 % to 11 % in men . Female athletes are especially vulnerable because menstrual losses add to training‑related iron loss . Vegetarians, vegans and athletes with low energy availability may also struggle to meet their iron needs .

How Exercise Influences Iron and Ferritin

Exercise does not always raise ferritin. In fact, heavy training can deplete iron stores and lower ferritin. Several mechanisms explain this dual relationship:

1. Increased iron loss

Haemolysis: High‑impact activities like running cause “foot‑strike haemolysis,” in which red blood cells burst when the foot hits the ground. The released haemoglobin is removed from circulation, lowering haptoglobin and iron levels .

Sweat, urine and gastrointestinal losses: Athletes lose iron through sweat, microscopic bleeding in the gut and urine. Sweat can contain up to 22.5 µg of iron per litre, and runners may develop haematuria from bladder trauma . Combined, these losses can increase daily iron requirements by 70 % compared with sedentary individuals .

Menstrual blood loss: Women who train heavily often have low ferritin because menstruation compounds exercise‑related iron loss .

2. Inflammation and hepcidin

Exercise causes a temporary inflammatory response. Interleukin‑6 (IL‑6) released during hard workouts stimulates the liver to produce hepcidin, a hormone that blocks iron absorption and traps iron inside ferritin . Hepcidin levels peak 3–6 hours after exercise, reducing the amount of iron absorbed from meals or supplements . Chronic high‑intensity training can therefore suppress iron uptake.

3. Acute‑phase response

Ferritin itself is an acute‑phase protein. After intense or long events like marathons or Ironman races, ferritin may spike temporarily because of inflammation or muscle damage . A post‑race ferritin test may falsely suggest adequate iron stores when, in fact, iron is trapped and unavailable for haemoglobin synthesis. Athletes should therefore schedule iron tests on rest days.

4. Hormonal influences

Heavy training suppresses gonadotropin‑releasing hormone and lowers oestrogen and testosterone. Lower oestrogen may elevate hepcidin and impair iron absorption . Women with relative energy deficiency in sport (RED‑S) often exhibit elevated hepcidin and low ferritin despite normal dietary intake .

Recognising Low Ferritin and Iron Deficiency

Typical signs of iron deficiency or low ferritin include:

Fatigue, lethargy and poor recovery even after adequate rest .

Decreased endurance, heavy legs and shortness of breath during workouts .

Pale skin, dizziness, headaches and mood changes .

Frequent infections or feeling cold .

Since ferritin can rise after hard training, athletes should test iron status (serum ferritin, serum iron, transferrin saturation and haemoglobin) on a rest day. A ferritin level below 30 µg/L suggests low stores in most adults; endurance athletes preparing for altitude or high training loads should aim for ferritin ≥50 µg/L .

Nutrition and Training Strategies to Maintain Iron

There are a number of effective dietary, timing and training strategies to optimise iron absorption and support healthy ferritin levels—yet these vary depending on individual factors such as training load, menstrual status, gut health, diet type and inflammation.

To ensure your iron strategy is safe, evidence-based and tailored to your physiology, ➡️ Book a consultation with me

References

Badenhorst, C.E. et al. (2021) ‘Iron status in athletic females, a shift in perspective on an old paradigm’, Journal of Sports Sciences, 39(14), pp. 1565–1575. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2021.1885782.

Beard, J.L. (2001) ‘Iron Biology in Immune Function, Muscle Metabolism and Neuronal Functioning’, The Journal of Nutrition, 131(2), pp. 568S–580S. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/131.2.568S.

Björn-Rasmussen, E. et al. (1974) ‘Food Iron Absorption in Man: Applications of the Two-Pool Extrinsic Tag Method to Measure Heme and Nonheme Iron Absorption from the Whole Diet’, Journal of Clinical Investigation, 53(1), pp. 247–255. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI107545.

Cowell, B.S. et al. (2003) ‘Policies on Screening Female Athletes for Iron Deficiency in NCAA Division I-A Institutions’, International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 13(3), pp. 277–285. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.13.3.277.

Damian, M.-T. et al. (2021) ‘Anemia in Sports: A Narrative Review’, Life, 11(9), p. 987. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/life11090987.

Domínguez, R. et al. (2018) ‘Effects of an Acute Exercise Bout on Serum Hepcidin Levels’, Nutrients, 10(2), p. 209. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10020209.

Fensham, N.C. et al. (2022) ‘Sequential Submaximal Training in Elite Male Rowers Does Not Result in Amplified Increases in Interleukin-6 or Hepcidin’, International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 32(3), pp. 177–185. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2021-0263.

Fortuny, J. et al. (2021) ‘Use of intravenous iron and risk of anaphylaxis: A multinational observational post‐authorisation safety study in Europe’, Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 30(10), pp. 1447–1457. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.5319.

Ganz, T. (2013) ‘Systemic Iron Homeostasis’, Physiological Reviews, 93(4), pp. 1721–1741. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00008.2013.

Hurrell, R. and Egli, I. (2010) ‘Iron bioavailability and dietary reference values’, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(5), pp. 1461S–1467S. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.28674F.

Kardasis, W. et al. (2023) ‘The IRONy in Athletic Performance’, Nutrients, 15(23), p. 4945. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15234945.

McCormick, R. et al. (2020) ‘Refining Treatment Strategies for Iron Deficient Athletes’, Sports Medicine, 50(12), pp. 2111–2123. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01360-2.

McKay, A.K.A. et al. (2020) ‘Influence of Periodizing Dietary Carbohydrate on Iron Regulation and Immune Function in Elite Triathletes’, International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 30(1), pp. 34–41. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2019-0131.

Mountjoy, M. et al. (2023) ‘2023 International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) consensus statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs)’, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57(17), pp. 1073–1098. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2023-106994.

Peeling, P. et al. (2007) ‘Effect of Iron Injections on Aerobic-Exercise Performance of Iron-Depleted Female Athletes’, International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 17(3), pp. 221–231. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.17.3.221.

Saunders, P.U. et al. (2013) ‘Relationship between changes in haemoglobin mass and maximal oxygen uptake after hypoxic exposure’, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 47(Suppl 1), pp. i26–i30. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092841.

Sim, M. et al. (2019) ‘Iron considerations for the athlete: a narrative review’, European Journal of Applied Physiology, 119(7), pp. 1463–1478. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-019-04157-y.

Solberg, A. and Reikvam, H. (2023) ‘Iron Status and Physical Performance in Athletes’, Life, 13(10), p. 2007. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/life13102007.

University of Giessen, Department of Exercise Physiology and Sports Therapy, Institute of Sports Science, Giessen, Germany et al. (2024) ‘Approaches to Prevent Iron Deficiency in Athletes’, German Journal of Sports Medicine, 75(5), pp. 195–202. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5960/dzsm.2024.607.

Vinchi, F. et al. (2019) ‘Intravenous Iron Promotes Low-Grade Inflammation in Anemic Patients by Triggering Macrophage Activation’, Blood, 134(Supplement_1), pp. 957–957. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2019-132235.

Weißenborn, A. et al. (2018) ‘Erratum zu: Höchstmengen für Vitamine und Mineralstoffe in Nahrungsergänzungsmitteln’, Journal of Consumer Protection and Food Safety, 13(2), pp. 251–251. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00003-018-1162-0.

Wouthuyzen-Bakker, M. and van Assen, S. (2015) ‘Exercise-induced anaemia: a forgotten cause of iron deficiency anaemia in young adults’, The British Journal of General Practice, 65(634), pp. 268–269. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp15X685069.

Zhu, Y. and Haas, J. (1997) ‘Iron depletion without anemia and physical performance in young women’, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 66(2), pp. 334–341. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/66.2.334.

Zoller, H. and Vogel, W. (2004) ‘Iron supplementation in athletes—first do no harm’, Nutrition, 20(7–8), pp. 615–619. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2004.04.006.

Blogs and Insights