⚖️ Weight Loss

Lifestyle

Intermitting fasting

October 28, 2025

Share

Rather than focusing on what you eat, time-restricted eating (TRE) focuses on when you eat, aligning meals with the body’s natural circadian rhythm. Research suggests that this timing matters just as much as food quality when it comes to blood-sugar regulation, appetite, and overall metabolic health.

What Is Time-Restricted Eating?

TRE limits food intake to a set window each day—typically between 4 and 12 hours—while fasting during the remaining hours.

The goal is to eat during the body’s active, daylight phase when metabolism is most efficient, and allow the digestive system to rest overnight.

Unlike calorie-restricted diets, TRE doesn’t prescribe what to eat, but when to eat it. This helps many people naturally reduce calorie intake, improve glucose control, and feel more in tune with natural hunger signals.

Main Types of TRE

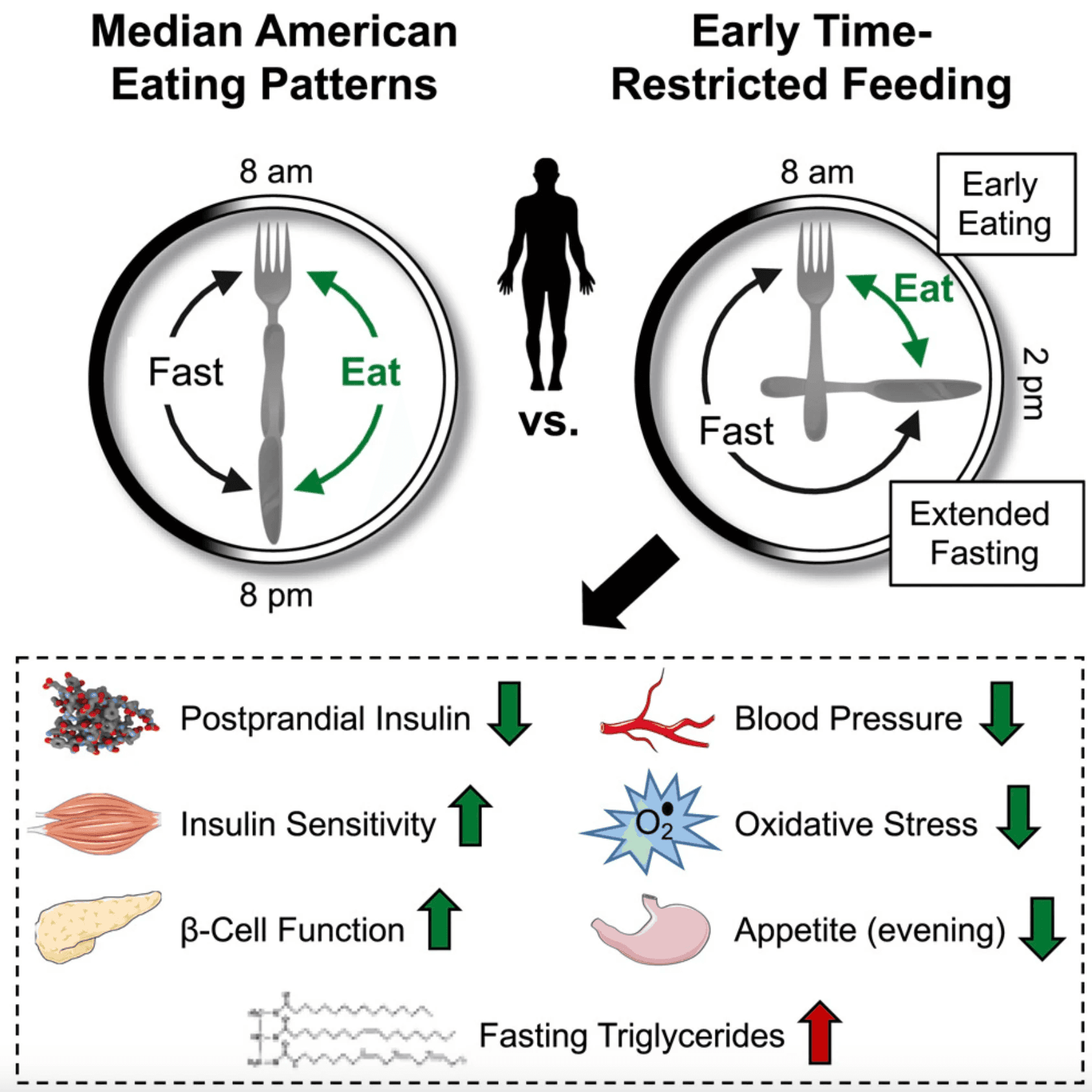

Early Time-Restricted Feeding (eTRF)

Eating earlier in the day, usually between 8 a.m. and 2–3 p.m.. This aligns with peak insulin sensitivity and may offer the strongest metabolic benefits.Late or Self-Selected TRE

Eating later, such as 12 p.m.–8 p.m., or choosing a personal 8–10 hour window that fits lifestyle or social needs. While slightly less optimal metabolically, it’s often easier to maintain.Short Windows (4–6 hours)

Highly compressed eating schedules (e.g., 3–7 p.m.) can produce quick results but may increase fatigue or dizziness and are difficult to sustain long-term.Moderate Windows (8–10 hours)

Popular and practical patterns such as 16:8 or 10-hour TRE balance flexibility with measurable benefits for weight, glucose, and blood pressure.Extended Windows (12 hours or more)

A 12-hour window (e.g., 8 a.m.–8 p.m.) is close to normal eating habits and shows little additional benefit, so research tends to focus on shorter windows.

What Research Shows

Metabolic and weight outcomes

Eating earlier in the day consistently improves insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and appetite regulation.

Early TRE combined with a calorie-controlled diet enhances fat and weight reduction, though may slightly reduce lean mass.

In people with metabolic syndrome, a 10-hour window reduced body weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol.

Early TRE with resistance training led to greater weight loss than late TRE, with similar gains in muscle strength.

A recent Nature Medicine trial found that when diet quality was controlled, early, late, and self-selected windows produced similar short-term outcomes, suggesting flexibility may be more important than exact timing.

(Sutton et al. 2018).

Exercise synergy

Pairing TRE with resistance or high-intensity training supports fat loss while preserving muscle. Early TRE combined with exercise tends to show the best body-composition results.

Sleep and well-being

Most studies show neutral or slightly improved sleep and mood, with some participants reporting better energy and focus.

Risks and Considerations

Muscle loss can occur if protein or resistance exercise is insufficient.

Very short windows (4–6 h) can limit nutrient intake and increase fatigue.

Adherence may decline over time; flexible windows work best.

Women, older adults, and people with chronic conditions should personalise their fasting approach.

Conclusion

Time-restricted eating is a flexible, evidence-based strategy that supports healthy weight, blood sugar, and cardiovascular balance.

The best-researched and most effective version is early TRE, finishing meals by mid-afternoon. However, 8–10 hour self-selected windows are more sustainable and still offer meaningful benefits.

TRE isn’t a quick fix—it’s a lifestyle rhythm that works best when combined with nutrient-dense foods, regular movement, and adequate rest.

Aligning meals with your body’s natural clock may be one of the simplest ways to support lasting metabolic health.

To help you choose an eating pattern that’s aligned with your unique physiology, ➡️ Book a consultation with me.

Reference list:

Bohlman, C. et al. (2024) ‘The effects of time-restricted eating on sleep in adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials’, Frontiers in Nutrition, 11, p. 1419811. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1419811.

Boyd, P. et al. (2022) ‘Time-Restricted Feeding Studies and Possible Human Benefit’, JNCI Cancer Spectrum, 6(3), p. pkac032. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/jncics/pkac032.

Cienfuegos, S. et al. (2020) ‘Effects of four-hour and six-hour time-restricted feeding on weight and cardiometabolic health: a randomized controlled trial in adults with obesity’, Cell Metabolism, 32(3), pp. 366-378.e3. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2020.06.018.

Domaszewski, P. et al. (2022) ‘Effect of a six-week time-restricted eating intervention on the body composition in early elderly men with overweight’, Scientific Reports, 12(1), p. 9816. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13904-9.

Dote-Montero, M. et al. (2025) ‘Effects of early, late and self-selected time-restricted eating on visceral adipose tissue and cardiometabolic health in participants with overweight or obesity: a randomized controlled trial’, Nature Medicine, 31(2), pp. 524–533. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03375-y.

Gabel, K. et al. (no date) ‘Effects of 8-hour time-restricted feeding on body weight and metabolic disease risk factors in obese adults: A pilot study’, Nutrition and Healthy Aging, 4(4), pp. 345–353. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3233/NHA-170036.

Habe, B. et al. (2025) ‘Comparing the influence of early and late time-restricted eating with energy restriction and energy restriction alone on cardiometabolic markers, metabolic hormones and appetite in adults with overweight/obesity: per-protocol analysis of a 3-month randomized clinical trial’, Nutrition & Metabolism, 22(1), p. 85. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-025-00984-3.

Haganes, K.L. et al. (2025) ‘Maintenance of time-restricted eating and high-intensity interval training in women with overweight/obesity 2 years after a randomized controlled trial’, Scientific Reports, 15(1), p. 14520. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95743-y.

Hays, H.M. et al. (2025) ‘Effects of time-restricted eating with exercise on body composition in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, International Journal of Obesity, 49(5), pp. 755–765. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-024-01704-2.

Heath, R.J., Welbourne, J. and Martin, D. (2025) ‘What are the effects of time-restricted eating upon metabolic health outcomes in individuals with metabolic syndrome: A scoping review’, Physiological Reports, 13(9), p. e70338. Available at: https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.70338.

Manoogian, E.N.C. and Laferrère, B. (2023) ‘Time-restricted eating: What we know and where the field is going’, Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 31(Suppl 1), pp. 7–8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23672.

Maruthur, N.M. et al. (2024) ‘Effect of Isocaloric, Time-Restricted Eating on Body Weight in Adults With Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Trial’, Annals of Internal Medicine, 177(5), pp. 549–558. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7326/M23-3132.

Sutton, E.F. et al. (2018) ‘Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even Without Weight Loss in Men with Prediabetes’, Cell Metabolism, 27(6), pp. 1212-1221.e3. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.04.010.

Wilkinson, M.J. et al. (2020) ‘Ten-hour time-restricted eating reduces weight, blood pressure, and atherogenic lipids in patients with metabolic syndrome’, Cell Metabolism, 31(1), pp. 92-104.e5. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.11.004.

Blogs and Insights