🥦 Nutrition & Nutrients

Glycose

Fat gain

January 9, 2026

Share

Glucose (the basic sugar unit) is a vital fuel for our cells, but eating too much sugar can overwhelm the body’s normal pathways, leading to surplus energy being stored as fat and setting the stage for health issues down the line.

The journey of sugar through your body starts from immediate energy use (glycolysis) and short-term storage (glycogen); when those stores overflow, the body converts excess sugar into fat (lipogenesis).

Glucose as Fuel: Glycolysis and Glycogen Storage

Glucose is the body’s preferred energy source. As soon as glucose from your diet enters your bloodstream, your cells begin breaking it down through glycolysis – a series of reactions that convert glucose into pyruvate, yielding energy in the form of ATP (adenosine triphosphate). This energy powers everything from muscle contractions to brain function. Under normal conditions, most of the glucose you consume is used to meet immediate energy needs. For example, after a high-carb meal, many tissues (especially muscles) will ramp up glucose burning to fuel their activities.

Any glucose that isn’t needed right away doesn’t just float around; your body stores it for later. The storage form of glucose is glycogen, a large polymer of glucose molecules. Insulin (a hormone we’ll discuss more soon) helps excess glucose get stored as glycogen in the liver and muscles. However, glycogen storage capacity is limited – once liver and muscle cells pack in all the glycogen they can (only a few hundred grams, roughly), they can’t accept more. Think of glycogen like your body’s short-term battery: it can be charged up with extra glucose, but it has a finite size. Endurance-trained athletes can have somewhat bigger “batteries” (larger glycogen stores) than sedentary people, but the space is still limited.

Storing glucose as glycogen serves an important purpose: between meals or during exercise, glycogen can be broken back down into glucose to keep your blood sugar stable and supply energy to tissues. But what happens if you’ve already topped off your energy needs and filled your glycogen stores, and yet you’re still consuming more sugar? This is where the story takes a turn.

Excess Glucose Overflow: From Glycogen to Fat (Lipogenesis)

When glycogen stores are full and your cells have all the energy they need, the body must find another place for incoming glucose. It doesn’t simply waste the excess sugar; evolution has equipped us to store surplus energy for later times of need. So, the body activates an alternative pathway: converting that extra glucose into fat. This process is known as de novo lipogenesis – essentially, making fat from scratch out of carbohydrates.

In the liver, excess glucose is channeled into fat synthesis. Through a series of biochemical steps, glucose (or its metabolites from glycolysis) is converted into fatty acids. These fatty acids are then combined with a glycerol backbone to form triacylglycerols (TAGs) or triglycerides. The liver packages these triglycerides and either stores them in its own cells or ships them out into the bloodstream as VLDL particles (very-low-density lipoproteins) to be deposited in adipose tissue (body fat). In simpler terms, when you’ve eaten more sugar than you can burn or stash as glycogen, your body turns the surplus into fat and tucks it away in fat cells.

This is why people say eating too many carbs or sugars can lead to fat gain – it’s biochemically true that excess carbohydrate can be converted into body fat. Notably, this conversion to fat doesn’t happen only because you ate sugar; it happens because you ate beyond your energy needs. If you frequently consume more calories (from sugar or otherwise) than you burn, those extra calories will be stored, often as fat. Sugar just makes it particularly easy to overconsume calories, and sugary foods can rapidly fill glycogen stores and spill over into fat production. In fact, if energy needs are met and glycogen is maxed out, the body will convert the leftover glucose into fatty acids and store it in adipose tissue.

Blood Sugar Spikes and Insulin’s Response

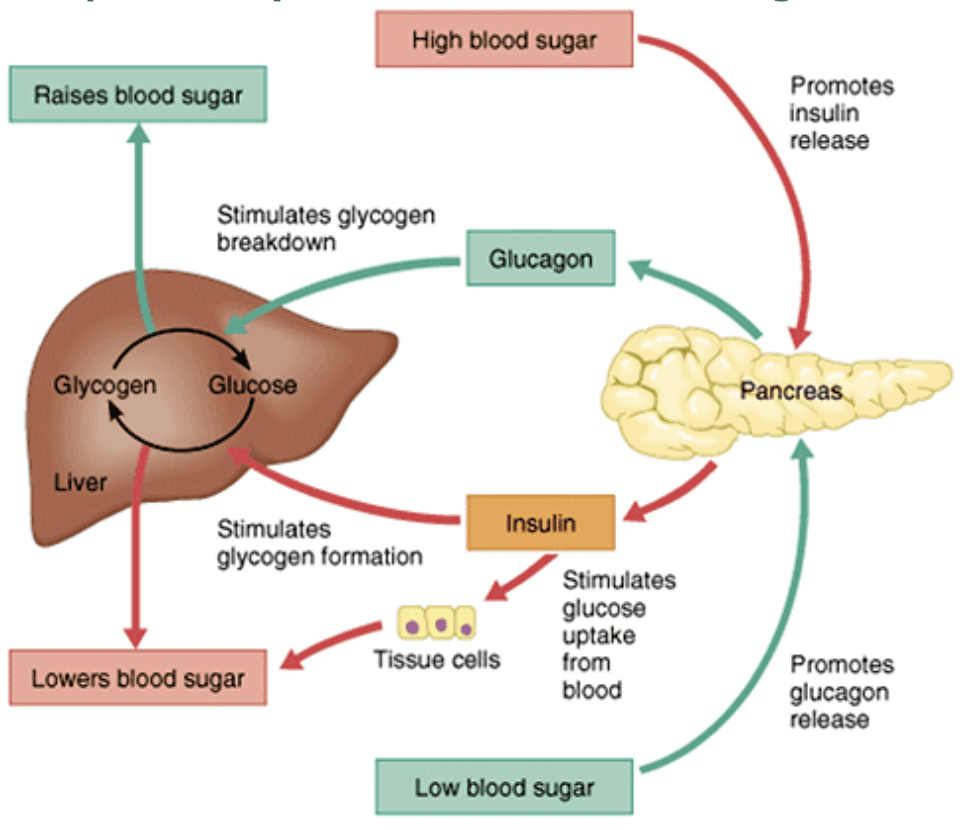

Let’s rewind a bit to the moment you eat that sugary snack: as glucose floods into your blood, blood sugar levels begin to rise. Your body maintains a tight control on blood glucose, because too-high or too-low levels can be dangerous. The pancreas swiftly responds by releasing insulin, a hormone that acts as the key regulator of blood sugar. Insulin’s job is to tell cells, “Hey, there’s plenty of glucose available – take it up!” When insulin binds to receptors on muscle and fat cells, it triggers those cells to absorb glucose from the bloodstream. Inside the cells, that glucose will be used for energy or turned into glycogen for storage. This process quickly brings blood sugar back down into the normal range (about 70–100 mg/dL).

Insulin doesn’t just help store glucose as glycogen; it’s often called a “storage hormone” because it promotes the storage of nutrients in general. Insulin stimulates pathways like glycolysis (burning glucose for energy) and lipogenesis (creating fat), while simultaneously telling the body to stop making new glucose (it suppresses gluconeogenesis). In the context of a high-sugar meal, the surge of insulin helps convert that sugar into stored forms (glycogen or fat), preventing blood glucose from staying dangerously high. The immediate effect of a big sugar intake, therefore, is a quick spike in blood sugar followed by an insulin-driven dive as glucose is hustled into storage. Many people have experienced this as a “sugar rush” followed by a “crash” – you get a burst of energy, and then later feel weak or hungry once blood sugar dips again.

What if this cycle repeats too often? Constantly eating lots of sugar means your insulin levels have to spike repeatedly to cope with the onslaught of glucose. Over time, cells can start to lose sensitivity to insulin’s signal – a condition known as insulin resistance. Initially, the body compensates by producing even more insulin (imagine the pancreas shouting louder and louder at the cells to respond). However, this compensation can’t go on forever. Persistently high insulin and blood sugar levels can eventually exhaust the system, setting the stage for metabolic troubles.

Long-Term Impacts: Fat Buildup, Insulin Resistance, and Metabolic Disorders

Regularly consuming excess sugar doesn’t just lead to a few extra pounds – it can fundamentally change how your metabolism works. One of the first changes may be increased fat storage.Consistently high sugar and insulin promote the buildup of visceral fat (the fat around your organs, often concentrated in the belly region) because the body is in constant “store energy” mode. You might notice weight gain or increasing waist size as a visible sign of this process. Meanwhile, some of that newly made fat can deposit in the liver itself, leading to fatty liver (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD). The liver is literally filling with fat that it created from surplus sugar.

As mentioned, insulin resistance can develop when insulin is chronically elevated. Insulin resistance means cells (in muscles, fat, and the liver) become less responsive to insulin – they don’t take up glucose as readily. This leads to higher blood sugar levels over time, because glucose lingers longer in the bloodstream. The pancreas works overtime to pump out even more insulin to force blood sugar down, but this is a vicious cycle. Eventually, insulin resistance can progress to prediabetes and then type 2 diabetes, when the pancreas can no longer keep blood glucose in check. High-sugar diets are strongly associated with an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes. In fact, studies have found that people who consume a lot of added sugars have a higher prevalence of insulin resistance and diabetes, and reducing sugar intake can improve these conditions.

But the problems don’t stop at diabetes and fatty liver. The combination of excess fat storage, insulin resistance, high blood sugar, and high blood triglycerides (remember those VLDL particles full of sugar-converted fat) can snowball into metabolic syndrome – a cluster of conditions including abdominal obesity, elevated blood pressure, high blood sugar, high triglycerides, and low HDL cholesterol. This syndrome significantly raises the risk of cardiovascular disease. In essence, chronic sugar overload can wreak havoc on your metabolic health, contributing to obesity, hypertension, heart disease, and more . Researchers have noted that calorie for calorie, diets high in added sugars tend to cause more insulin resistance and metabolic problems than diets high in other carbs.

To summarize the cascade: eating too much sugar fills up your short-term energy stores and then turns on fat production. The result is increased body fat (and possibly fatty liver), higher blood fats (triglycerides), and an overworked insulin system. In the long run, this pattern can lead to insulin resistance, where your cells stop listening to insulin, causing chronically high blood sugar and insulin levels. That is a stepping stone to type 2 diabetes. Moreover, having high insulin and fat levels in the blood can drive inflammation and blood pressure up, contributing to conditions like heart disease. It’s a domino effect that often starts quietly – you don’t feel the biochemical hustle and bustle – but over years, it can manifest as significant health issues.

Key Takeaways

Glucose is vital fuel: When you eat sugar, your body breaks it down via glycolysis to fuel cells, and stores extra as glycogen in liver and muscle for later use . This is the normal, healthy way your body manages blood sugar and energy needs.

Storage is limited: Glycogen reservoirs fill up quickly. Once they’re full, any surplus glucose has to be dealt with differently . Your body won’t just leave glucose floating in blood – it must either use it or store it.

Excess sugar turns to fat: When energy intake exceeds demand and glycogen can’t take more, the liver converts excess glucose into fatty acids, which get assembled into triacylglycerols (triglycerides). These fats are then stored in adipose tissue or in the liver itself . Overeating sugar essentially primes your body to increase fat stores.

Blood sugar spikes trigger insulin: A big sugar load causes a rapid rise in blood glucose, prompting a surge of insulin to shuttle glucose into cells and normalise blood sugar . Insulin helps store the excess (as glycogen or fat), but frequent spikes can lead to chronically high insulin levels.

Overload leads to insulin resistance: Persistently eating too much sugar forces your body into storage overdrive. Over time, cells become insulin resistant, not responding well to the hormone . This can result in consistently elevated blood sugar and insulin, often progressing to type 2 diabetes if not addressed .

Metabolic consequences: Chronic high sugar intake contributes to fat accumulation (weight gain, visceral fat, fatty liver) and a host of metabolic problems. These include insulin resistance, higher triglyceride levels, and inflammation, which together increase the risk of metabolic disorders like diabetes, heart disease, and NAFLD . In short, too much sugar over time pushes your body toward an unhealthy state.

Reference list:

DeFronzo, R.A., Ferrannini, E., Groop, L. et al. (2015) ‘Type 2 diabetes mellitus’, Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 1, 15019. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrdp201519

Gropper, S.S., Smith, J.L. and Carr, T.P. (2021) Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism. 8th edn. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Kahn, S.E., Hull, R.L. and Utzschneider, K.M. (2006) ‘Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes’, Nature, 444, pp. 840–846. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature05482

Nelson, D.L. and Cox, M.M. (2021) Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. 8th edn. New York: W.H. Freeman.

Rui, L. (2014) ‘Energy metabolism in the liver’, Comprehensive Physiology, 4(1), pp. 177–197. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4050641/

Softic, S., Cohen, D.E. and Kahn, C.R. (2016) ‘Role of dietary fructose and hepatic de novo lipogenesis in fatty liver disease’, Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 61(5), pp. 1282–1293.Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26856717/

Stanhope, K.L. (2016) ‘Sugar consumption, metabolic disease and obesity’, Current Opinion in Lipidology, 27(1), pp. 30–36.Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26600029/

Tappy, L. and Lê, K.-A. (2010) ‘Metabolic effects of fructose and the worldwide increase in obesity’, Physiological Reviews, 90(1), pp. 23–46.Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20086073/

Blogs and Insights