🥦 Nutrition & Nutrients

Fats

Investigations

December 29, 2025

Share

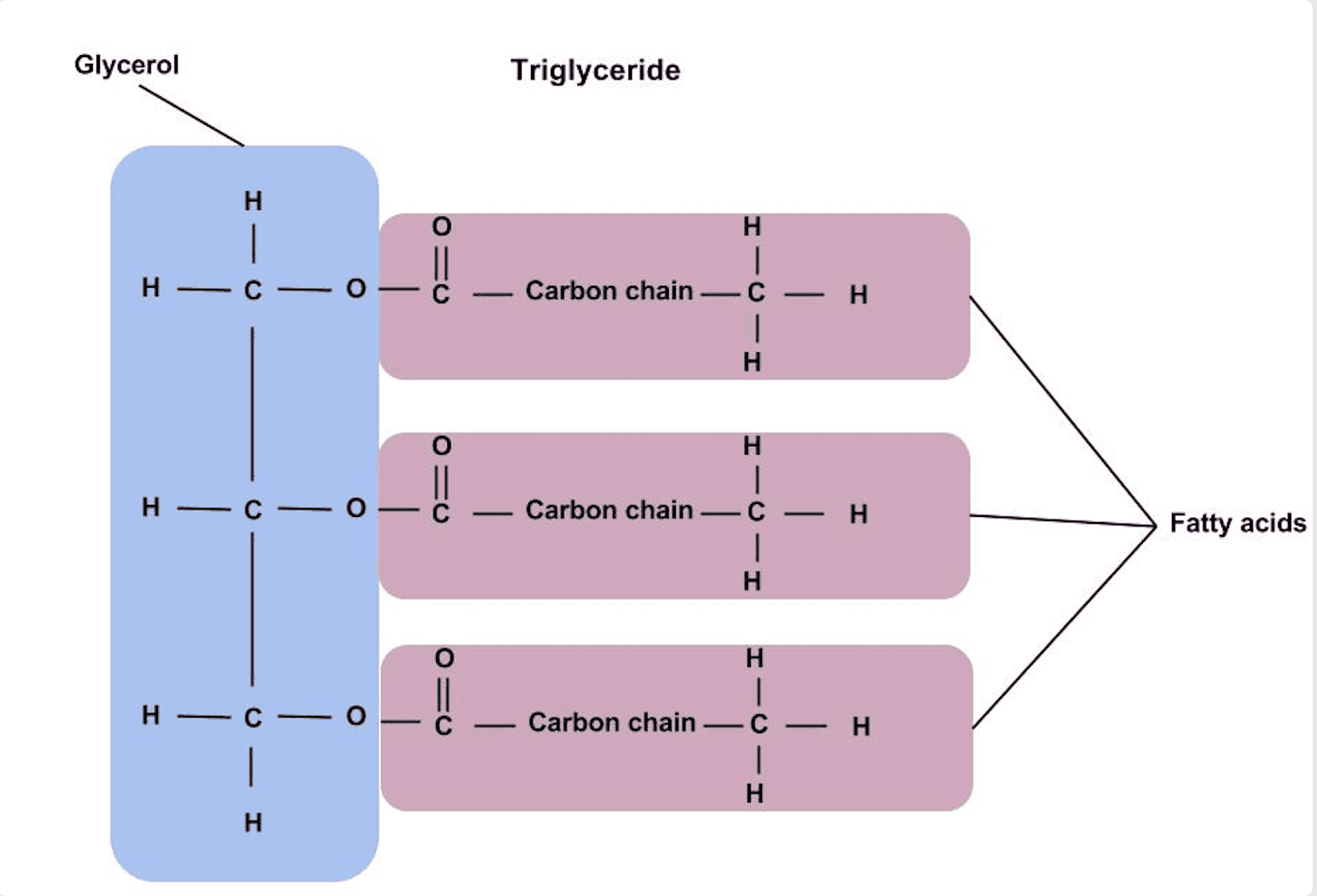

Fats are essential nutrients that provide energy, build cell structures and enable the absorption of fat‑soluble vitamins. Most dietary fat comes as triglycerides, composed of a glycerol backbone with three fatty acids attached. Depending on the arrangement of carbon–carbon bonds, fatty acids are classified as saturated, unsaturated or trans fats. These structural differences explain why some fats are healthier than others.

Structure and function

Fatty acids without double bonds are saturated; their straight chains pack closely and are solid at room temperature. When one or more cis double bonds are present, the chain bends, producing monounsaturated (MUFA) and polyunsaturated (PUFA) fats that remain liquid. Trans fats have at least one double bond in the trans configuration, so their chain stays straight like a saturated fat. Phospholipids built from these fatty acids form cell membranes, and sterols such as cholesterol insert between phospholipid tails and serve as precursors for steroid hormones (oestrogen, cortisol, testosterone etc). Lipids also supply concentrated energy and support the absorption of vitamins A, D, E and K.

Saturated fats

Saturated fats are abundant in animal foods—fatty cuts of meat, butter, ghee, lard and full‑fat dairy—and in certain plant oils such as palm and coconut oil. Because their straight chains reduce membrane fluidity, diets rich in saturated fat raise LDL (“bad”) cholesterol by decreasing LDL receptor activity. Historic feeding trials showed that replacing saturated fat with unsaturated oils lowers cholesterol levels. Contemporary analyses find that lowering saturated fat alone does not always reduce heart‑disease events; the benefit arises when saturated fat is replaced by unsaturated fats. Thus dietary guidelines advise limiting saturated fat and using liquid vegetable oils, nuts and seeds instead of butter or lard.

Healthy unsaturated fats

Monounsaturated fats (MUFA) have one cis double bond and are plentiful in olive oil, canola (rapeseed) oil, avocados, nuts and seeds. In prospective cohorts, plant‑derived MUFAs from olive oil and nuts were associated with lower coronary heart disease risk than MUFAs from animal foods. Clinical trials confirm that replacing saturated or trans fats with plant‑based MUFAs lowers LDL and triglyceride levels. Polyunsaturated fats (PUFA) contain two or more double bonds. Omega‑6 fats (linoleic acid) are common in sunflower, corn and soybean oils, while omega‑3 fats include alpha‑linolenic acid from flaxseed, soy, canola and walnuts, and EPA/DHA from fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel and sardines. Replacing 5 % of energy from saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat ia shown to lower LDL cholesterol and coronary disease risk. Long‑chain omega‑3 PUFAs reduce triglycerides and modestly lower cardiovascular risk. Eating fish twice weekly and using vegetable oils rich in linoleic and alpha‑linolenic acids help achieve these benefits.

Trans fats

Trans fats form during partial hydrogenation, when cis double bonds in unsaturated oils are flipped to trans configuration to solidify the oil . Even small amounts of industrial trans fat elevate LDL cholesterol and suppress HDL cholesterol . They were widely used in margarine, fried fast foods and packaged baked goods but are now banned or restricted in many countries. The World Health Organisation recommends that trans fats provide less than 1 % of energy. Small amounts of naturally occurring trans fats in dairy and ruminant meat are not considered harmful .

Cholesterol and dietary guidance

Cholesterol is a sterol produced in the liver and used to stabilise cell membranes and synthesise steroid hormones. Foods high in cholesterol, such as eggs and shellfish, exert a modest influence on blood cholesterol compared with saturated fat. Modern guidelines therefore focus on reducing saturated fat and trans fat while encouraging unsaturated fat consumption. In practice, choosing unsaturated fats—olive oil, nuts, seeds and oily fish—while limiting fatty meats, butter, ghee and processed baked goods helps improve lipid profiles and lower cardiovascular risk .

References:

Ahmed, S., Shah, P. & Ahmed, O. (2023) Biochemistry, lipids. StatPearls [online]. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525952/

Antoni, R. (2023) ‘Dietary saturated fat and cholesterol: cracking the myths around eggs and cardiovascular disease’, Journal of Nutritional Science, 12, e97. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10495817/

Marchand, V. (2010) ‘Trans fats: what physicians should know’, Paediatrics & Child Health, 15(6), pp. 373–375. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2912739/

Zong, G. et al. (2018) ‘Monounsaturated fats from plant and animal sources in relation to risk of coronary heart disease among US men and women’, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 107(3), pp. 445–453. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqx063

de Roos, B. & Geleijnse, J. M. (2025) ‘Dietary polyunsaturated to saturated fat ratio and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of feeding trials’, Nutrients, 17, 3059. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12483678/

Duan, Y. et al. (2025) ‘Dietary fatty acids and metabolic health: contributions of saturated, monounsaturated, polyunsaturated and trans fats’, Nutrients (editorial). Available at: https://www.mdpi.com

Blogs and Insights